In reading Moe’s Thermally Active Surfaces in Architecture, I found his connections made in relation to the human body most interesting.

The body must constantly modify its internal temperature through its own heat production and by absorbing the temperature of its surroundings in order to maintain thermal comfort. As the surrounding room temperatures increase, the rate of evaporative loss, also known as sweat, increases. When bodies come in contact with an architectural surface, conduction becomes the primary mode of heat transfer. However, this rarely happens that bodies are in direct contact with thermally active surfaces and objects. The body itself is a thermally active, hydronic heating and cooling system that transfers heat energy to and from its core to its skin.

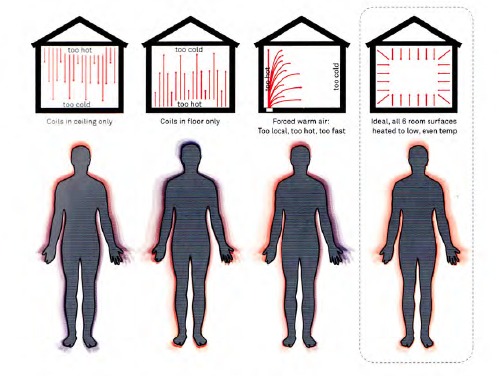

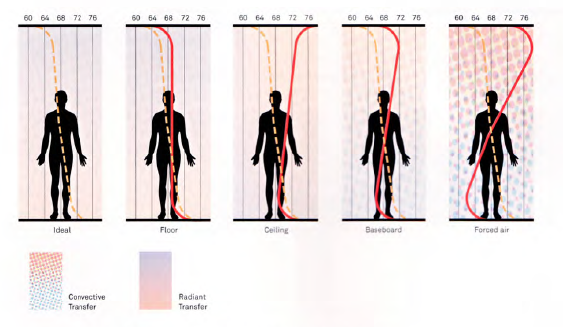

Certain thermal conditioning systems and configurations yield varying temperature profiles and corresponding levels of human comfort. The relationship between the temperature profiles in space and a human body demonstrates that various radiant sources yield more even temperature profiles and the lowest precipitation of thermal asymmetries in and around the body. This may be because of drafts, infiltration, the buoyancy of air, and the volatility of convection patterns in a space of thermal comfort. To fully account for human comfort, thermal calculations need to include surface temperatures of a space. James Marston Fitch noted that it is optimal to have thermally active surfaces on six sides of a space as show in the diagram below: